Success of mythical proportions

Brokerage unicorns are faking it, while incumbent brokers discover digitization

This is the inaugural article in my invite-only newsletter. I've been a blogger since 2009, but I'm excited by the new combination of longform writing, delivery to emails instead of on a website, and keeping the distribution to a small set of industry participants. Now, let me get this started provocatively.

The core value proposition of UberFreight and Convoy to carriers and shippers is not technology but capital injection (from the investors who bought the tech story). Meanwhile, real digitization is starting up in earnest at the incumbent brokers, making it unlikely these two unicorns will ever become dominant.

I'll push this forward with three arguments:

UberFreight and Convoy claim to disrupt the brokerage industry through technology. But that technology hasn't delivered reduced cost of sales, better gross margin, or better operating ratios. You'd be tempted to say that makes it useless. But their “tech” has suceeded in nudging investor perception from classifying them as brokers (i.e. valuations of ~2 times annual revenue) to software companies (i.e. valuations of ~12 times annual revenue).

If we ignore the tech story, the real reason for their fast growth is that they give away cash. For their shipper customers and carrier subcontractors, UberFreight and Convoy are like a drunk buying everyone drinks at the bar. You can make a lot of friends that way. By my math (shown below), they give away at least an additional 40 cents for every $1 they touch.

Steady advances at the incumbent brokers look a lot more like real tech. They are streamlining sales, raising sell rates, lowering buy rates, and taking out headcount from the back office. Everyone who has the resources is gearing up for brokerage that is more automated, more instrumented, and more data driven.

UberFreight and Convoy are faking it.

I make and sell software. But the software market is flooded with fakes, so part of my job is to watch for the signals of fakery. With that in mind, checkout how Convoy describes itself in their About Us page:

Convoy is the most efficient digital freight network, using machine learning and automation to connect shippers and carriers to move millions of truckloads, saving money for shippers, increasing earnings for carriers, and eliminating carbon waste for our planet.

I call this “branding masquerading as product”. You can't buy “network” from Convoy. You can pay them to transport goods, or be paid by them to transport goods. Their marketplace or network is just conceptually how they want to be seen, not what they actually are paid to do. Convoy and UberFreight are trucking brokers. They both have brokerage licenses. Their revenue comes from selling a transport service, for which they are liable. They make a profit by purchasing capacity from a carrier for lower than their sell rate. So why go to the trouble to cross-dress as a tech business?

The sophistry has a purpose: to market Convoy as a software business, not a brokerage. And the only reason to do that is to inflate the value of the business to potential investors. Financial markets will value a software business at 12x their annual revenues, whereas a trucking broker will get less than 2x revenue. This is such a large gap that even falling in-between could be lucrative. Convoy can make the maximalist claim of complete automation and even if investors just discount it they'll end up with a huge valuation lift. In a recent secondary market listing for their shares, Convoy made the case to would-be investors:

In 2015, Convoy started the world’s first digital freight network, connecting shipments with carriers to move millions of truckloads, leading a transformation of the old ways of moving freight with the most efficient digital freight network in the industry.

Convoy claims to be the most efficient and automated network. But that should translate into superior economics somewhere: lower cost of sales, wider gross margins, or improved conversion ratio (i.e. EBIT divided by gross revenue). Convoy doesn't disclose these numbers, although its widely known that their operating margin is negative. But since UberFreight is public, we do have those figures and they are largely the same story: UberFreight has worse gross margins and also conversion ratios than any brokerage its size. Nowhere is tech improving the fundamental economics of their business the way it does, for example, at JB Hunt.

So my contention is this: Convoy and UberFreight are succeeding by faking that they are tech companies. In reality, they are brokers with about as much reliance on inhouse developed tech as their peers. Their play is simply to convince investors to value the company's revenue (and growth) as if it will someday be a software business. Even if they can't hit the usual 12x revenue valuations they'll likely get something higher than 2x revenue typically seen for a broker. And this is working: Convoy had ~$300m in revenue in 2018 and yet was valued at $1 billion. These are still sizable brokerages worthy of respect as such. But that's not all they claim to be, and so I call BS.

The Drinks Are on Them.

Convoy and UberFreight surely have grown quickly. Convoy may be near $1 billion in annual revenue. UberFreight had $852 million in revenue over the last 12 months. For both these businesses, that's zero revenue to >$800 million annual revenue in just five years. How did they do it?

The main value Convoy and UberFreight bring to their shipper and carrier partners is their capital: they give away cash. I also think this is obvious: they receive X amount of revenue from shippers, pay Y amount out to carriers, and since X < Y they subsidize the flow by adding Z amount of investor cash. If Z is large, it means either the shipper underpaid, the carrier was overpaid, or both. And the bigger Z becomes, the more we should see it as the real source of growth.

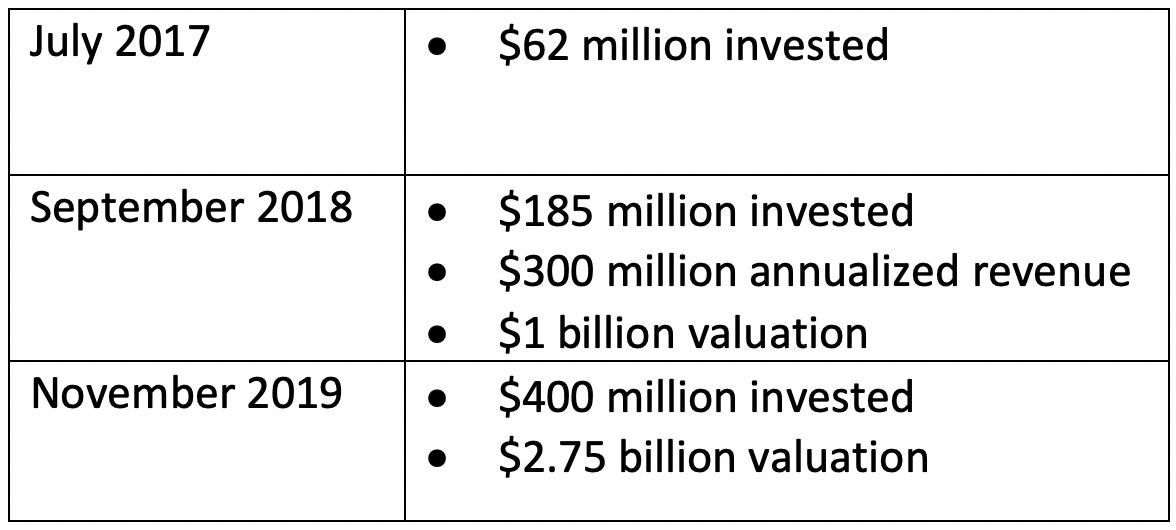

How much cash did they give away to grow so fast? For Convoy, we can estimate this by looking at revenue, revenue growth, and investment timing. This gets a bit complicated, but here are some facts about Convoy:

Now here are the assumptions I'm adding. Because they raised money, we have to assume most of what they raised previously was spent by the next investment. Let's say $50 million in the first period, and $185 million in the second. Also, I assume the were roughly doubling revenue per year, which implies ~7% month-on-month growth of revenue. So the first investment took place when they had $115 million of annualised revenue, then the second at $300 million, and the third at $816 million. This would align to the increase in valuation between the second and third investments described above.

The upshot is that between rounds 1 and 2 Convoy earned $240 million in revenue against $50 million of the investor capital. And between investments 2 and 3 their revenues were $620 million to which they added another $185 million of investor capital.

For UberFreight its even simpler to estimate because they have been reporting their Freight division's revenue and gross margin quarterly since 2018. Since Q3 2018, they had $1,396 million in revenue and paid out $1,780 million to carriers, meaning their investors supplemented $384 million.

But don't most businesses earn a profit? Yes, the normal brokerage gross margin is 12-15%. So, when Convoy or UberFreight go below 12% they are already giving cash to someone (compared to the other brokers).

After all the math, the total figures look like this:

Convoy: from July 2017 to November 2019 they probably earned $735 million in revenues, should have made at least $88 million in gross profit, but instead spent all of that plus $235 million more in investor cash with their carrier base. Total “free cash” effect was $323 million on revenues of $735 million, meaning either their shippers or their carriers got $0.43 extra for every $1 they would normally pay or be paid.

UberFreight: from July 2018 to June 2020 they earned $1,396 million in revenue, should have made at least $167 million in gross profit, but instead spent all of that plus $384 million more in investor cash with their carrier base. Total “free cash” effect was $551 million on revenues of $1,396 million, meaning either their shippers or their carriers got $0.40 extra for every $1 they would normally pay or be paid.

Again, it’s worth noting that loss-leading for growth is fine as a strategy. See Amazon if you have doubts. But what I'm doing here is making it clear that giving the shipper or carrier free cash is really the driver for Convoy and UberFreight growth, not their tech somehow creating efficiencies, great experiences, or whatever.

Unicorn Season

This quote summarizes how outsiders see the incumbent brokers and their assumed domination by the new digital broker unicorns:

The tech companies’ growth has come at the expense of smaller, traditional brokers, says Lee Klaskow, an analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. “You have these old school guys smoking a cigarette with a Rolodex and a phone.”

When I started TNX one of my founding beliefs was contrarian to the tech scene: brokers are not going to be disintermediated. Their margins might shrink a little, but they fight for every bit of market share and will adapt and adopt and stay ahead of outsiders in part because outsiders underestimate the challenges of this industry.

That was 2016. Today, I see the incumbent brokers digitizing at all levels: from the smaller companies like Edge Logistics who have bootstrapped digital freight matching processes, to the fast-growing mid-stack like Arrive Logistics or Traffix who are building at-scale digital pipelines from quote to booking, and placing it at the core of their business. And at the top end of the market we see companies like Nolan, Echo, and Redwood all taking digitization seriously with new teams, partners, and operating models. Of the biggest players, let's just point out a counterexample to Convoy & UberFreight. JB Hunt's incremental improvements in Marketplace 360 have been yielding financial benefits in back office productivity, the way real tech investments are supposed to work. That may lead to valuation lifts via the old-fashioned way of better earnings. None of these businesses have created a breakthrough, insurmountable advantage from digitization. But at this pace they'll set new competitive expectations at each tier of the market in just a few years.

TNX has been commissioning a research agency to interview top-100 brokers about their digitization (or lack of), and I'll share those insights in a later article. But for now, I think its obvious that every broker who has the resources is investing into digitization of their core quote, buy, track, and payment processes. And that suggests the unicorns will have trouble securing a true differentiation when the free money stops flowing.