When Scale Matters

Part 1 of a 4 part series on platform as a business model in logistics

This is the first a series of articles on platforms as a business model for the logistics sector. It connects with a three hour podcast in which I discussed the same topic with my friend Märten Veskimäe. Check out the podcast at Logistics Tribe on Apple or Spotify.

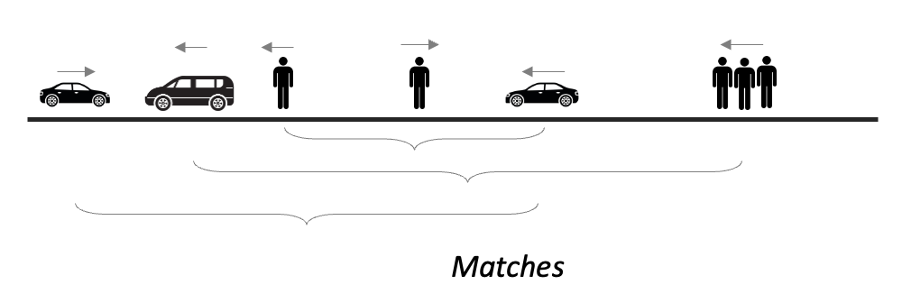

Platform scale (i.e. how many members it has) is often described in terms of density. For example, Loadboards like DAT and Timocom, or digital brokers like Convoy and UberFreight talk about their platform’s density. What is this about? Why don’t normal businesses (like a WMS vendor such as Manhattan Associates) talk about densities? The key here is that platforms facilitate matches or interactions between the platform members, rather than acting as the counterparty to them directly. Traditional businesses are trying to date you, platforms are trying to set you up on a date. And that match-making means having two sides (or more) that align on the key terms of the match. As a working example, imagine a ride-hailing platform like Uber or Lyft operating in a world with one street. The riders and the drivers each has one variable that matters: where they are at on the street. Let’s start with just one driver and one rider. If they are close enough, it’s a match.

The given wisdom is that riders will accept wait times up to 5 minutes without issue, and after that they increasingly risk cancelling the request for a ride. The platform operator doesn’t want that, so they try to add both more drivers and more riders. You can do the math: it’s a finite street so the more of each side that joins, the more likely they are to be closer, the less likely someone cancels. Nirvana. But wait…

Heterogeneity

Ride sharing drivers have preferences about where they end their trip, not just where they start. So, the matching is actually about finding an alignment on starting point (to pickup in under 5 minutes) while also ensuring drivers end where they like. So, there are two dimensions to match. Oh, and sometimes the riders are a group and they need a larger vehicle. So, three factors to match.

What you see here is that each time a dimension is added (the wait time to pickup, the end location, the size of the vehicle, etc.) there must be more members on the platform to achieve the same likelihood of a successful match. This aspect is crucial to logistics platforms because our industry’s matches are occurring on highly heterogenous objects. Take the canonical example of “Uber for Trucks” companies like Convoy, Sennder, or UberFreight. They don’t have 3 dimensions like ride hailing. They have at least 20, maybe more like 50. Each of those dimensions of potential match requires yet more members to have any chance of matching. We can all think of examples where a pool of hundreds of shippers or tens of thousands of carriers still doesn’t have the low-emissions flatbed tractor-trailer with extra insurance and a night-driving permit and experience driving in winter roads up north. It takes essentially a whole industry to cover all these edge cases, and so it needs almost a whole industry on a platform to make effective matches.

Why Platforms Compete on Scale

What this obviously leads to is a mission to achieve more scale, and a lazy assumption that a platform with more scale is ipso-facto more valuable. That is why density features in the home page text for logistics platforms. But I think most people in our industry miss that heterogeneity of matching factors is what makes scale relevant. Think about the first example for a moment: the single road world with only three factors (time to pickup, region of drop-off, and size of vehicle). In each dimension there is a level of density that satisfies the members, such as 5 minutes to pickup. Further density (say 1 minute to pickup) doesn’t add value. The fact that each dimension has a satisfying level of density indicates that scale overall eventually stops adding value.

Let’s say a company like Uber has large scale in a city. Once their competitor platform has achieved minimum coverage of these three factors the additional scale of Uber is irrelevant. In platform competition, the leader’s scale advantage is fundamentally tied to how many factors are required for a match between its members. Beyond the minimum density, additional scale is not convertible to higher margins. In sectors like logistics, where the match events typically involve very high dimension count, this gives a true advantage for large scale platforms (i.e. ones with the most members). But this advantage is predicated on a few other crucial points.

Scale Advantage Requires Diversity

If the scale of logistics platform delivers advantages because it covers more possible dimensions to match its members on, then it seems to assume that diversity of members is correlated with count of members. If a platform essentially has depth over diversity (for example if it has a lot of flatbed carriers but no high security ones) then scale leadership between platforms offers less competitive advantage.

Scale Advantage Requires Data Capture

As simple as this sounds, if a platform doesn’t capture data about a dimension it likely cannot match its members on it. They are out of business now, but years back there was a company called Loadfox in Europe that promised to match part loads with capacity by “playing Tetris with the cargo” to achieve better trailer fill rates. But checking their API specifications you’d realize that they don’t ask for cargo dimensions (just the volume as cubic meters). If they didn’t know about the dimensions, they damn well couldn’t match member partloads with them, hence any scale advantage they could have achieved would be negated. This lack of proper data capture is the norm, not the exception. Can you search DAT for what loads require drivers to unload? Can you search Truckstop by how many chains or straps are needed for the flatbed? Can you search Timocom by the language the driver must speak to take a load? All are examples of dimensions crucial to the match but not actually facilitated by the three platforms. Lost scale advantage.

Multi-Homing as the Great Commoditizer

But the most important way in which platforms lose their scale advantage is by member multi-homing. If you are wondering “what is multi-homing” it’s a sign of how weak the industry’s expertise is in building (or buying into) platforms as the business model. Multi-homing happens when platform members are using multiple competing platforms simultaneously. If all sides of the platform do this, it eliminates any scale advantage for the larger platform and in effect makes the set of competing platforms into a collective (and commoditized) set of channels to achieve matches. Let me show how this happens right now in logistics platforms. Consider the USA loadboard space. Most dry van carriers will have a subscription to both DAT an Truckstop. Brokerages will also have a subscription on DAT and Truckstop. If both sides of the match (capacity and demand) are on both platforms and listing their load or truck on both platforms, then these platforms are fully commoditized in terms of scale for that match event. The same occurs in Europe between Trans-eu and Timocom. These platforms in effect lose their pricing power that nominal scale advantage could give them because their members are so easily multi-homing. Preventing multi-homing is a primary directive for platform builders. Conversely, achieving multi-homing is one of the most effective ways to avoid platform pricing power for the members, and may even be encouraged by the smaller platform. Don’t the lesser platforms in our industry make it awful easy to dual list? That is the underdog’s push for multi-homing to negate their scale deficit.

The True North of Platform Leadership

Under the scale competition is an assumption about network effects, i.e. everytime a new member joins the platform it is more valuable for the existing (and future) members. But this isn’t sharp enough thinking: network effects differ tremendously in their magnitude and type. For example, is it cross-side network effects or same-side? In Timocom I don’t see that a new carrier helps the existing carriers. Rather new carriers help the forwarders, i.e. Timocom as a platform has mostly cross-side network effects.

But let me raise an issue no one seems to discuss. A new carrier on a loadboard adds value cross-side (i.e. to brokerages who may match with the new carrier). But it also is a swapping effect (a term I’m making up because I cannot find a clear definition elsewhere) because the new carrier creates its value by replacing the match with a less attractive existing carrier member. This mechanic (i.e. where a new member swaps into the match of an existing platform member to the advantage of the cross-side) is inherently limited in its scale potential because an existing member has to lose value for the new value to be created. The value changes may net out for the better, but it plateaus quickly. In contrast there are rare but real network effects that are simply additive. Rate benchmarking may be an example for logistics platforms: if all asset-operating carriers benchmarked their rates it’s not clear how a new rate addition would hurt anyone: the network effect is same-side and purely additive. This, I believe, is the key to creating permanent scale advantages in a platform both for the platform owner, via pricing power, and for its members via value-create. I say that because additive network effects are different than heterogenous match criteria. They don’t eventually get satisfied at some scale and then lose further competitive power. Nor are they like swapping effects where the net value nudges upwards at smaller and smaller increments as scale increases. Additive network effects might allow any platform scale increase to generate meaningful more value to the members. If you take nothing else from this article, just add this one question to your mental toolkit: is this logistics platform creating pure additive value with each new member or is it a swapping win-lose situation? Head to the purely additive ones if possible.

Scale and Competition with Members

As a final note, we should ask how scale helps platforms compete with their own members. Remember, platforms are intermediaries to the interaction. They are in a constant competition with their own members to deliver value-adding intermediation or risk that the members simply work directly. We see this all the time in logistics platforms, because (a) platforms extract value and (b) often the interactions are happening between parties who know one another and could, if they want, go off platform for direct dealing. Does scale help a platform avoid disintermediation? I don’t think so. Scale would matter most in places where novel matches occur, because then you need counterparty discovery. In other words, if most of my matches on a platform are with members I didn’t know previously it stands to reason that the platform will be hard to disintermediate. But logistics tends to occur between known counterparties. Even if they first meet each other via a platform (thanks to its immense scale) its likely they’ll do most of their value adding work after the initial meeting. While I think platforms compete with each other on scale (at least partially) I think they compete with their members on other factors such as standards setting and proprietary data that facilitates the interactions. I say more about these topics in part 2, but for now I think disintermediation is weakly defended by a logistics platform simply being larger.

Background Research

If this discussion does something for you, consider also checking out these sources that I found useful.

The Platform Delusion: Who Wins and Who Loses in the Age of Tech Titans

7 Powers

Acquired podcast: Platforms and Power (with Hamilton Helmer and Chenyi Shi)

The cold start problem

Platform Scale

Matchmakers: The New Economics of Multisided Platforms

https://hbr.org/2019/01/why-some-platforms-thrive-and-others-dont

https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication Files/18-032_d71914fe-d56c-42ad-ae20-deb5b979fab9.pdf

https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/57c7d6ed-ad52-11eb-9767-01aa75ed71a1

Quite possibly the definitive article on this topic for logistics. Nice work!

Jonah, as always, you make me think deeper about the role of technology in this industry. I learned a lot reading this and am excited about the rest of the series. Thank you for providing those resources at the end.